The Great Nicobar Project_A Case Study in Bureaucratic Correctness, Ethical Bankruptcy_Decode Journalism

The National Green Tribunal dropped a bombshell on Monday, clearing the way for the Great Nicobar Project by disposing of petitions that challenged its environmental clearances. While the NGT’s eastern bench insisted that “adequate safeguards” exist, a closer look at this ₹92,000 crore project reveals a troubling pattern of procedural shortcuts, ecological recklessness, and questionable treatment of indigenous communities.

Let’s be clear about what’s happening here: this isn’t just another infrastructure project. This is a massive intervention in one of India’s last pristine ecosystems, and the way it’s being pushed through raises serious red flags.

The Numbers Don’t Add Up

First, let’s talk about the budget. The project has ballooned from an initial estimate of ₹40,000-50,000 crore to ₹92,000 crore in just four years. That’s more than double the original projection. Recent reports suggest the port alone could cost ₹1 lakh crore. When a project’s costs spiral this dramatically before construction even begins, it’s worth asking: what else hasn’t been properly planned?

The Great Nicobar Project: A Convenient Approach to Tribal Rights

Here’s where things get particularly concerning. The Forest Rights Act (FRA) was enacted to protect tribal communities, yet it wasn’t implemented in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for 18 years after the 2004 tsunami. Why? Apparently because the Nicobarese and Shompen communities had “free access” to the forest and the lands were already designated as tribal lands.

But when this project came along and needed FRA clearances, suddenly the administration moved with remarkable speed. Within just 21 days of constituting committees under the FRA, authorities declared all land claims settled and announced that tribal communities had consented to hand over their forest lands. Twenty-one days to settle nearly two decades of unresolved claims? That’s not efficiency—that’s a rubber stamp.

The tribal councils of Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar didn’t stay silent. They wrote to authorities explicitly stating that their rights had not been settled and they had not consented to the land diversion. Yet the project marches forward anyway.

The Shompen: An Inconvenient Population

Let’s pause on the Shompen community. There are approximately 300 Shompen people who remain largely uncontacted. They have minimal exposure to outside diseases, modern lifestyles, or infrastructure. Nobody speaks their language fluently enough to communicate meaningfully with them.

So how exactly did the administration determine their consent? How do you consult with a community when there’s no shared language, no framework for meaningful dialogue?

Impact of the Great Nicobar Project: Death by a Thousand Cuts (or Ten Lakh Trees)

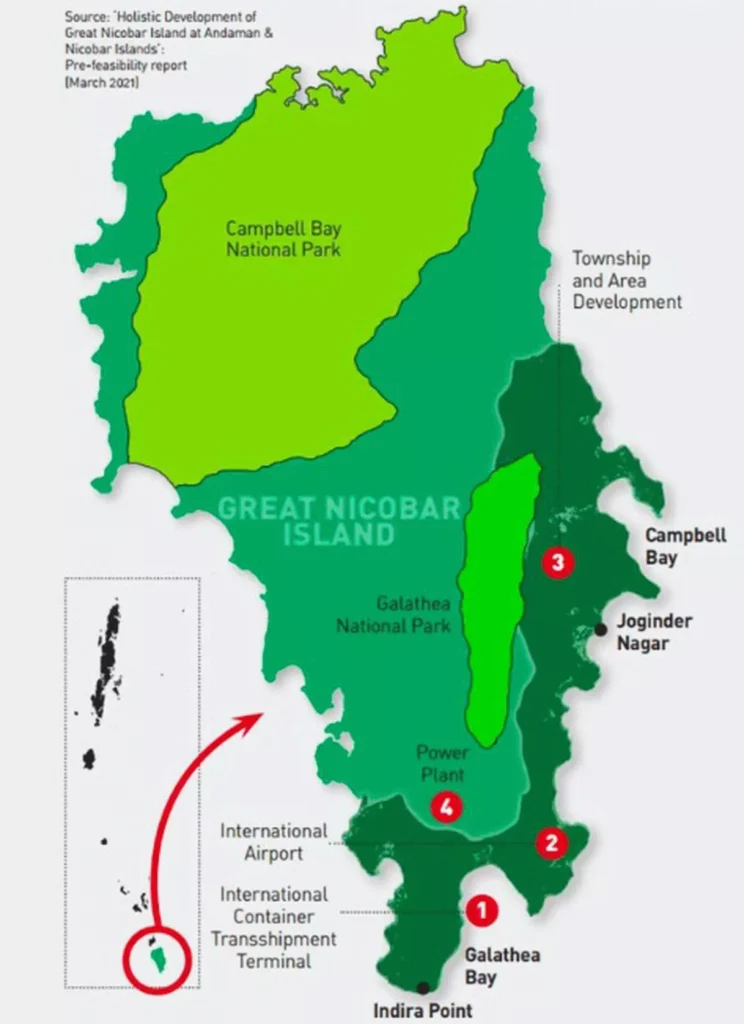

The scale of environmental destruction is staggering. The project requires clearing approximately 10 lakh trees from an island where 95% of the 920 square kilometers is still tropical rainforest. Only about 8,000 people currently live on Great Nicobar Island, with roughly 1,000 being indigenous residents.

The Great Nicobar Project: project plans to bring in 350,000 people from the mainland. Think about that ratio: the population would increase more than fortyfold. Even with the best intentions, that influx will require enormous amounts of water, generate massive quantities of waste, and inevitably push into areas beyond the designated 130 square kilometers.

In January 2021, the Government of India simply de-notified two wildlife sanctuaries—Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary and Megapode Wildlife Sanctuary—to make way for the project. Galathea Bay happens to be one of the world’s largest nesting sites for the Giant Leatherback Turtle and is part of India’s own National Marine Turtle Action Plan. The irony is almost too perfect: a government conservation plan sacrificed for a government development plan.

The Paperwork Smokescreen

Critics point out that while all the bureaucratic boxes have been ticked, the actual content of environmental impact assessments is deeply flawed. The conditions are described as “unimplementable” and “illogical.” New species are still being discovered regularly in this region—two new species were documented just in November 2025. The marine ecosystem remains almost completely undocumented, yet we’re proceeding as if we understand what we’re destroying.

This is what experts call an “unknown unknown” situation. We literally don’t know what we don’t know about this ecosystem, yet we’re comfortable wiping out 130 square kilometers of it.

Strategic Importance vs. Irreversible Loss

The NGT justified its decision partly on the project’s “strategic importance.” Fair enough—India has legitimate strategic interests in developing the Nicobar Islands. But strategic importance doesn’t exempt a project from following proper legal procedures or conducting genuine environmental assessments. It certainly doesn’t justify steamrolling over indigenous communities’ rights.

The real question is whether the Great Nicobar Project, executed in this particular way, is the only path to achieving those strategic goals. Could a smaller-scale development achieve similar objectives with less ecological damage? Were alternatives genuinely considered, or was this massive intervention simply the easiest option for contractors and politicians?

The Great Nicobar Project: What Happens Next?

The Calcutta High Court has scheduled a final hearing for the week beginning March 30, 2026. Meetings between the Tribal Council and district officials are planned to discuss potential village relocation and land claims—discussions that arguably should have happened years ago, before environmental clearances were granted.

The Union Shipping Ministry is planning “ground visits” as the project approval nears. One hopes these visits will involve more than photo opportunities and will include genuine engagement with the communities whose lives are about to be irrevocably altered.

The Reality Check

This project is probably going to happen. The legal momentum is too strong, the political will is there. But let’s not pretend this process has been ethical or transparent or respectful of the laws that exist specifically to prevent this exact scenario.

When the government ministry that’s supposed to protect tribal welfare is actively helping developers access tribal lands, the system is broken. Full stop.

The Great Nicobar project is basically a masterclass in how to pursue development while technically following the rules but completely missing the point of why those rules exist in the first place.

Future generations are going to look back at this and judge us. And by the time they do, the rainforest will be gone, the turtles displaced, the Shompen and Nicobarese communities forever changed. Some choices can’t be undone, and this is looking like one of them.