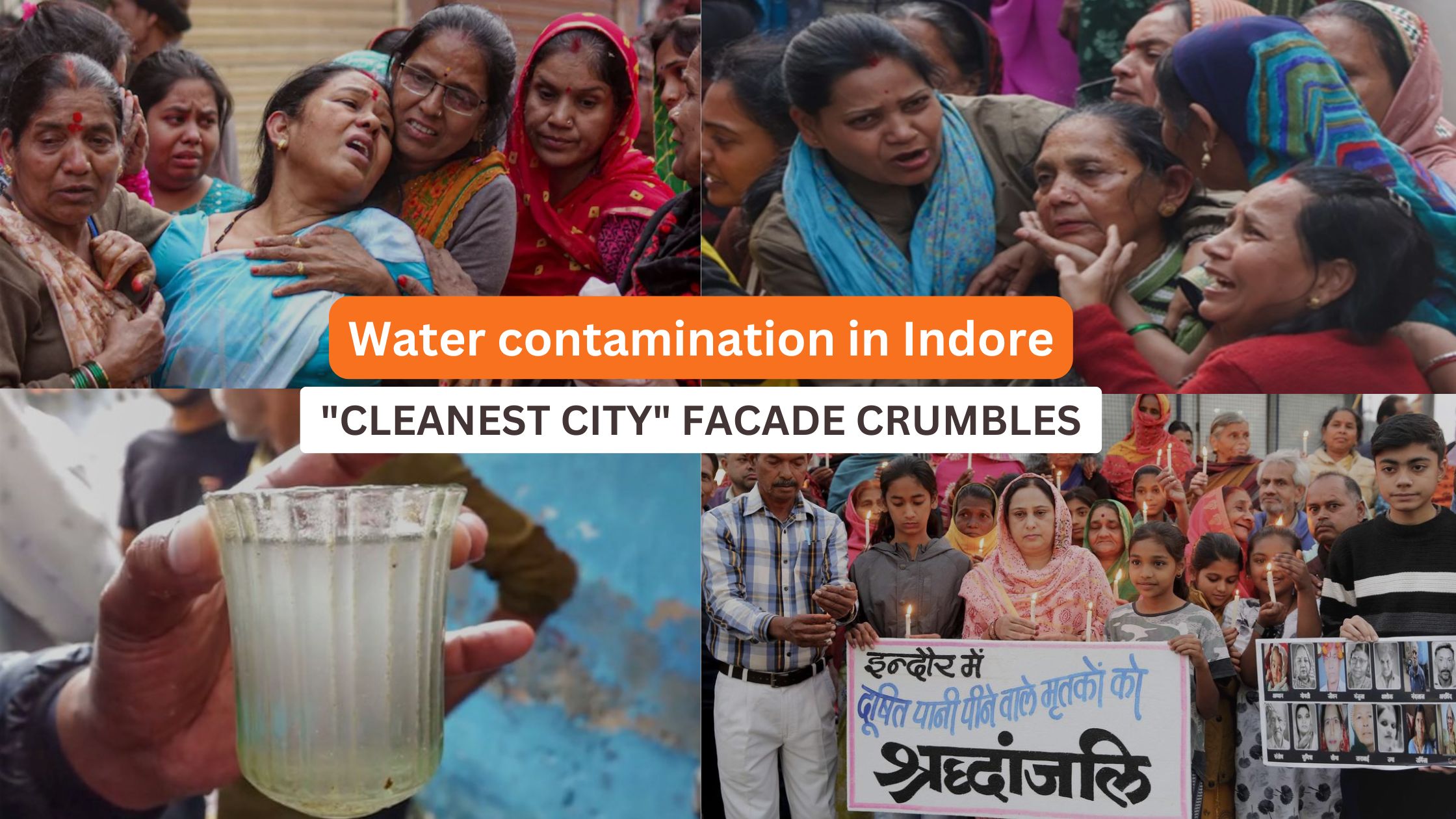

Water contamination in Indore, a city that prides itself for its “cleanest city” ranking, has claimed at least 18 lives and left over 1,400 citizens battling severe illness. The Bhagirathpura neighborhood has become the epicenter of a preventable tragedy where toxic drinking water contamination was not a natural disaster but it is a grim indictment of urban mismanagement.

How the contamination was discovered?

The investigation into this crisis reveals a shocking level of engineering negligence. Officials from the Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC) traced the source of the pathogen to a police outpost toilet. In a violation of basic civil engineering and sanitation protocols, the facility’s waste discharged into an open pit situated directly atop a primary freshwater pipeline.

This allowed raw sewage to infiltrate the potable water network over an extended period. As a result, the drinking water supply contaminated by sewage for a long time. Residents complained about the bad smell and discoloration of their tap water for a few days. Authorities remained idle until the local hospital noticed a sharp rise in patients with severe gastrointestinal disorders, high fevers, and abdominal pain.

What is the response of officials for this tragedy?

The administrative reaction has been a mix of damage control and belated medical intervention. District Collector Shivam Verma announced a ₹2 lakh ex-gratia payment for the families of the deceased—but no amount of compensation can justify the loss of life caused by such fundamental engineering malpractice and state negligence.

While the Chief Medical and Health Officer (CMHO) mobilized 200 field teams to distribute ORS and zinc tablets to nearly 2,745 households, these measures are reactionary band-aids on a systemic wound. While the state focuses on “chlorinating” the water now, it fails to address why officials permiteed such a lethal design flaw to exist in a densely populated urban zone in the first place. According to a report by NDTV, a 67-year-old woman from Bhagirathpura, Parvati Bai Kondla, has been showing symptoms of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) which adds a terrifying layer to this crisis. This is because such families can now face medical bills upwards of ₹15 lakh for life-saving IVIG therapy.

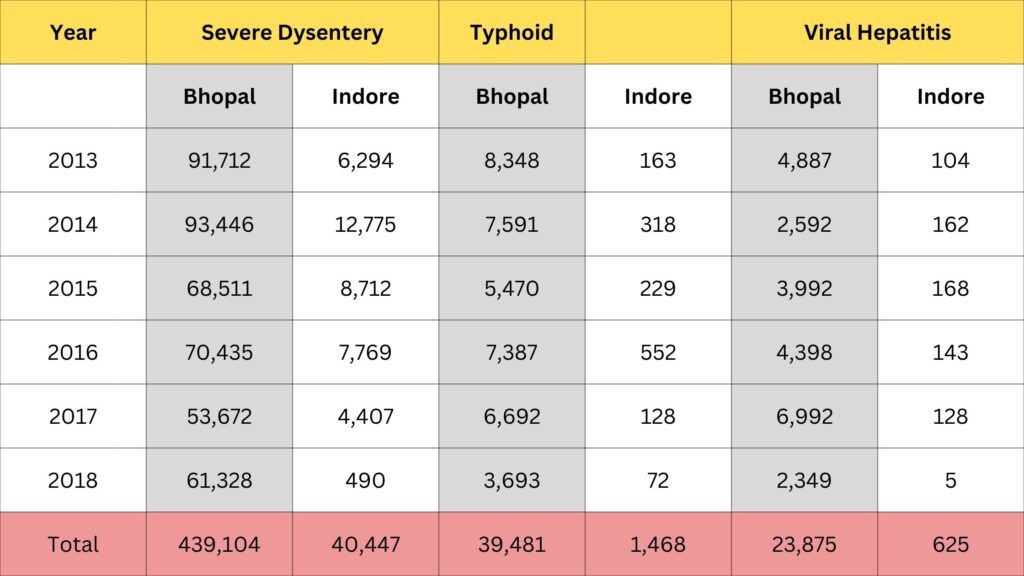

Indore Tragedy is not the only case; Bhopal faces the same fate too:

This horror is part of a broader, systemic pattern across Madhya Pradesh. Historical data suggests that the state’s urban centers are ticking time bombs of waterborne disease. Between 2013 and 2018, over half a million residents in Indore and Bhopal fell victim to contaminated water. Bhopal’s record is particularly harrowing, with over 4 lakh cases of severe diarrhea reported in that window. The Indore tragedy is merely the latest, most lethal manifestation of a long-standing refusal to prioritize safe water infrastructure.

Not constrained by a lack of Funding:

The most infuriating aspect of this disaster is that it was never a matter of scarcity. According to the 2019 Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report, both municipal bodies sat on massive piles of unspent cash. While Indore’s infrastructure was failing, the IMC left a staggering ₹1,215 crore of its water-service budget unutilized. This proves that the lack of resources didn’t caused these deaths in Bhagirathpura, but it was due to a total absence of political will and administrative competence.

Drinking Water Crisis is a System created Disaster:

As Magsaysay Award winner Rajendra Singh, a water conservative, rightly points out, this is a “system-created disaster.” The practice of laying fresh water lines adjacent to sewage pipes to cut costs is a recipe for homicide.

“Indore’s contaminated drinking water crisis is a system-created disaster. To save money, contractors lay drinking water pipelines close to drainage lines. Corruption has ruined the entire system. The Indore tragedy is the result of this corrupt system,” Rajendra Singh, a renowned water conservationist & Ramon Magsaysay Award winner, quoted as saying by PTI. “The year-on-year decline in groundwater levels in Indore is the most worrying. I visited Indore for the first time in 1992. Even then, I had asked how long the city would depend on water from the Narmada river?” Singh said.

The catastrophe is the inevitable result of a dishonest procurement process and a city that has prioritized PR-driven cleanliness awards over its falling groundwater levels. Even though Indore’s workers sweep the streets “everyday”, the city’s infrastructure is deteriorating, and its residents are paying the price with their lives.

This tragedy serves as a sobering reminder that a city cannot be genuinely “clean” if its most fundamental infrastructure is based on shortcuts and corruption. The grief of families in Bhagirathpura is currently testing the “Indore Model” of cleanliness, and the findings imply that the city’s fixation with rankings has come at the expense of its citizens’ lives.