Several Indian states are scheduled to hold elections between 2026 and 2027. As the elections approach, the debate of freebies and welfare schemes has intensified. Whether it’s free electricity, subsidised rations, or direct cash transfers, the promise of “freebies” has become an integral part of Indian electoral politics. However, the economic cost of these free schemes is often deeply hidden. Elections are scheduled to be held in many Indian states in 2026-27. Everyone’s attention is focused not only on which party will win or lose, but also on what free schemes each party will announce.

What is a Freebie in politics? Who Pays for them?

For some time now, freebies have become a cornerstone of Indian elections, whether it’s free bus services, free electricity, direct cash transfers, or subsidized rations. However, the economic cost of these schemes is often concealed.) But freebies offered based on caste or religion often serve merely as a tool for “vote-bank” politics. While social welfare is essential for a developing country, “unnecessary freebies” offered without a strong financial foundation can lead to a debt trap, increasing the burden on taxpayers for future generations. In contrast, welfare based on income (Targeted Subsidies) ensures that the taxpayer’s money reaches those who genuinely need it to escape the poverty line.

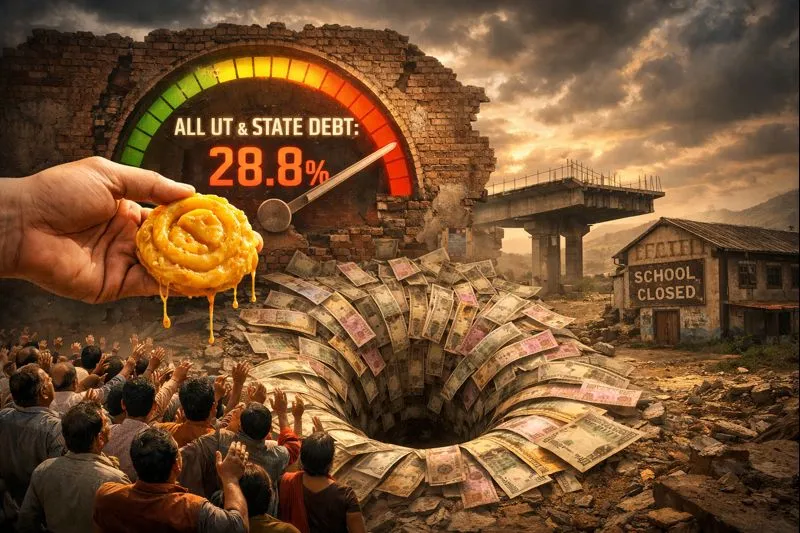

Fiscal Snapshot: Per Capita Debt and GSDP (2025 Projections)

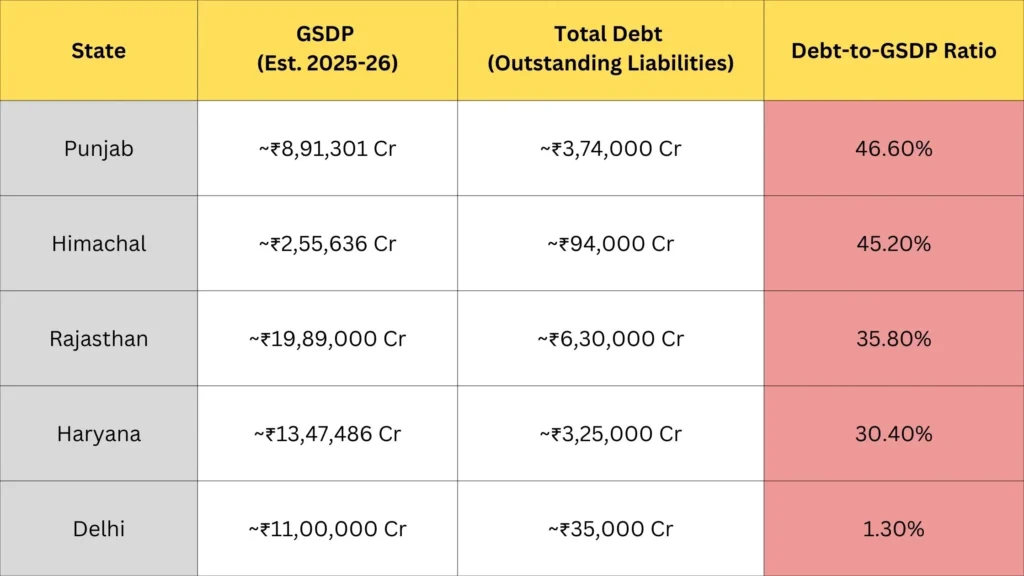

The “debt-to-GSDP” ratio is the most important metric for assessing a state’s financial health. It measures how much a state owes relative to the size of its economy. While reviewing the following data, please note that the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) committee recommends a target of 20%. To understand the scale of this issue, we examined the financial health and per capita debt situation of some states:

1. Punjab: The Debt Capital

With a debt-to-GSDP ratio nearing 46%, Punjab remains the most fiscally stressed state in India. It spends nearly 107% of its revenue receipts on “committed expenditure”—salaries, pensions, and interest payments—and massive power subsidies.

If we discuss Per Capita Debt: With a population of roughly 3 crore, the debt per resident is approximately ₹1,24,000. That means every child born in Punjab today starts life with a debt of over one lakh rupees.

2. Himachal Pradesh: A Growing Crisis

Himachal’s debt has ballooned recently, moving from 37% to an estimated 42.5% of its GSDP. The state’s limited industrial base and high reliance on central grants make its populist promises particularly risky.

For a population of roughly 75 lakhs, the debt per person stands at approximately ₹ 1.25 lakh, making it one of the highest in the country.

3. Rajasthan and Haryana: A Middle Path

* Rajasthan: After years of massive populist schemes (such as the Old Pension Scheme and free electricity), Rajasthan’s debt is around ₹78,000 per capita, accounting for a population of 80 million. This represents approximately 31.7% of Rajasthan’s GSDP.

* Haryana: More stable in comparison. Haryana’s debt-to-GSDP ratio is 24.2%. With a population of 30 million, per capita debt is around ₹108,000. While this ratio is lower than Punjab’s, the higher per capita debt reflects heavy borrowing for infrastructure.

4. Delhi: The Fiscal Outlier

Delhi presents a unique case. Because it is a Union Territory with limited “state-like” liabilities (the Union Government pays for its police and significant portions of pension), it maintains a massive Revenue Surplus. Its debt-to-GSDP is negligible (under 5%), and per capita debt remains the lowest among these five.

The Impact on Taxpayers and Growth

When a state like Punjab spends its budget on free electricity rather than new bridges or schools, it creates a vicious cycle:

Low Capital Expenditure:

Punjab has experienced a drop in capital expenditure, or the amount of money used to build assets. This will result in fewer jobs and slower growth for upcoming generation.

Inflationary Pressure:

States frequently raise fuel, diesel, and alcohol taxes in order to control their mounting debt. These inflations has a direct effect on middle-class people’s finances.

Interest Burden:

States like Himachal Pradesh and Punjab are currently using a large amount of their income to pay interest on past-due loans, leaving very little money for actual government.

Lessons for the People: Becoming a “Smart Voter”

The common man often thinks freebies are “gifted” by political parties. In reality, you pay for them in three ways:

1. Higher Indirect Taxes: If the state provides free water, it often increases the tax on petrol, diesel, or property taxes for homes. You aren’t getting anything for free; you are just paying for it through a different pocket.

2. Inflation: When a government borrows heavily to fund cash transfers, it puts more money into the market without increasing production. This leads to a rise in the prices of milk, vegetables, and LPG.

3. Quality of Life: If you get ₹1000 a month but your child’s government school has no roof or your local hospital has no medicines because the state is broke, you have lost more than you gained.

As we move further into 2026, the “Revadi” (freebie) culture is no longer just a political debate—it is an economic emergency. In states like Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, per capita debt is likely to continue rising if the “Revadi culture” is allowed to persist, which will ultimately lead to the collapse of public services. Making sure that “free” does not mean “financially bankrupt” is a challenge for 2026 and beyond.